A Brief History of Fatbikes

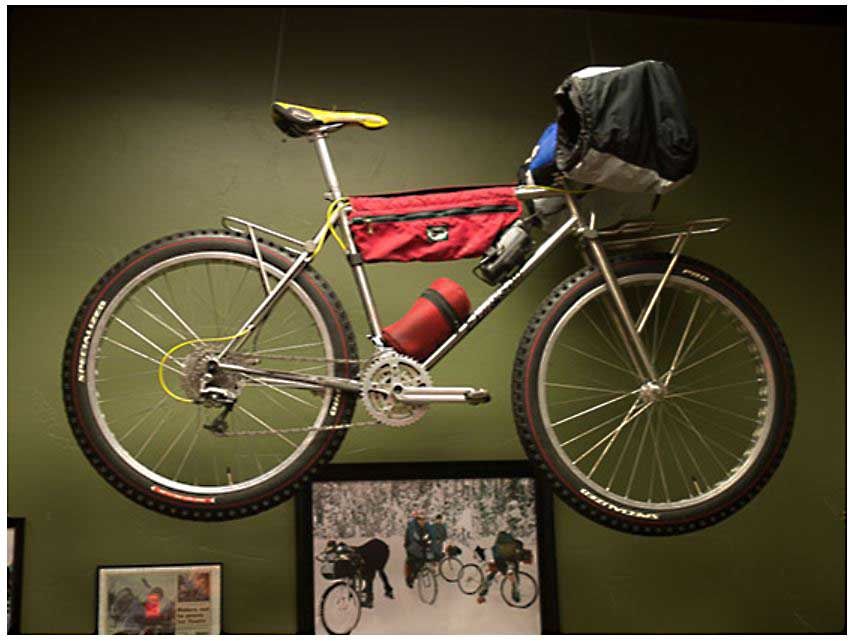

10 ago 2014La bici con cui Mike Curiak ha vinto la prima edizione ufficiale dell'Iditasport in Alaska: telaio artigianale Willits di Wes Williams modificato per ospitare cerchi Remolino e copertoni da 3 pollici.

Fatbikes have gained attention as the fastest growing segment of the bicycle industry this year, and for good reason. They've ridden the length of continents, across the snowy state of Alaska in winter, and along unique sections of coastline all around the globe. In the last few months, several fat tire vehicles have even appeared at the South Pole by means of human power, one of which was actually a tricycle! While fatbikes are capable of extreme all-terrain conquest, they also entice riders with their go-anywhere capacities on a more local scale. Midwestern urban explorers fight midweek blues by riding the river banks of the Mississippi, gunning out of town on weekends to ride and race groomed snowmobile trails. Fatbikes make light work of Coloradan jeep tracks, rocky Pennsylvanian singletrack, and Arizonan arroyos. In places like Anchorage, Alaska, where I am living for the winter, fatbikes play a central role in four-season commuting and recreation. Ten years ago, almost none of this existed.

The development of the conventional mountain bike is essential to the genesis of the modern fatbike. In the 1970s and 80s, groups of ingenious riders in California and Colorado modified singlespeed balloon-tire cruisers with a wide range of gears, powerful cantilever brakes, and durable lightweight components. Like never before, early all-terrain bikes were able to explore new routes, both up and down the mountain. Mass manufacturing and broad distribution helped the mountain bike explode on the market in the early 1980s, and by 1986, mountain bikes outsold road-racing and road-touring bikes. Adventurous riders explored deep into the backcountry, scouting new roads and trails, while others took to the streets and discovered that wide tires and an upright position make a comfortable urban commuter or cross-country tourer. Most importantly, mountain bikes enlivened cyclists with a new lens. With the ability to ride so many more places, the once finite resource of smooth pavement was replaced by an infinite universe of back roads, logging tracks, mining roads, and hiking trails. But limitations remained, especially on rocky terrain, soft surfaces, and steep grades. Since the late 1980's, mountain bikes have developed through suspension, lighter materials, and improved geometry, but most advancements have focused on the ability to conquer rough terrain at speed (i.e. mountain biking). Fatbikes attempt to solve the unique challenge of riding on a diverse range of surfaces, including sand, mud, and snow.

The history of the modern fatbikes includes two contemporaneous stories of development in Alaska and southern New Mexico. As mountain bikes arrived in shops in the 1980s, customizations for riding on sand and snow were quick to follow. In 1987, the first Iditabike event challenged riders to travel 200 miles of Alaskan backcountry in winter, following snowmobile and dog mushing trails. The course followed the first section of the historic Iditarod dog mushing trail to Nome, another 1000 miles further. Conditions along the trail range from rideable frozen crust — the result of daily freeze-thaw cycles — to a mélange of soft snow, glare ice, and liquid water overflow. Harsh conditions, and lots of walking alongside a bike in the snow challenged riders to improve their equipment for next year. A wider tire footprint was essential.

Individual rims were pinned or welded side by side, laced in tandem to a single hub, with two tires. With twice the footprint, the wider system allowed more riding and less walking. One notable experiment, called the “six pack,” even used three rims and tires side by side on both the front and the rear of a custom frame.

The tandem rim concept was improved by removing the two inner rim walls, to accept a single large-volume tire, which could operate at low pressure, and was lighter. Simon Rakower of Fairbanks, Alaska, modified rims in this manner for customers before entering production of the 44mm wide Snowcat rim. These wide, lightweight rims allowed the largest possible footprint, and fit within most conventional mountain bike frames. Most importantly, these rims were available off-the-shelf. They were standard equipment on winter bikes in Alaska for many years.

At about the same time, Ray Molina was exploring new terrain in southern New Mexico, and across the border into Mexico. Riding sand dunes and arroyos, Ray began manufacturing an 82mm wide rim in Mexico, along with a 3.5” tire to match, called the Chevron. He made several frames to accommodate the new equipment and testing took place at the Samalayuca sand dunes in Chihuahua, Mexico. At the Interbike trade show in late 1999, Alaskan Mark Groneweld made plans to bring Remolino rims to Alaska. Paired with his custom Wildfire Designs frame and a 3.0”-3.5” tire like the Nokian Gazzaloddi or the elusive Specialized Big Hit (both borrowed from downhill bikes), the first modern fatbikes were born. John Evingson, of Anchorage, Alaska, also built and raced highly refined custom bikes to fit Remolino rims and 3.0” tires.

Long-distance winter riding and racing continued through the 1990's in Alaska, and in 2000, Mike Curiak of Colorado won the first official Iditasport Impossible race to Nome, riding and pushing his bike over 1000 miles in just over 15 days. Mike's accomplishment may be the greatest proof of concept for fatbikes, ever. He rode a custom Willits frame made by Colorado builder Wes Williams, designed around Remolino rims and 3.0” tires. The bike is now on display at Absolute Bikes in Salida, Colorado, one of the best towns along the Great Divide Route. Until 2005, custom frames and hard-to-find rims and tires comprised the microscopic fatbike genre.

The Surly Pugsley changed the fatbike scene dramatically, providing the single greatest boost to availability and participation in the history of the fatbike. Released in an audacious purple color in 2005, along with the 65mm wide Large Marge rim and the 3.7” Endomorph tire, the modern fatbike era was born. The Pugsley was available to almost every bike shop in the country through Quality Bicycle Parts (QBP), a distributor with broad reach. The bike came as a bare frame and fork, and was intended to be completed with common mountain bike components, including standard 135mm hubs and a 100mm wide bottom bracket, also borrowed from downhill bikes. Following the release of the Pugsley, and subsequent sales growth, several other companies quickly joined the market. In 2007, pioneering a symmetrical aluminum frame with ultra-wide hubs (165mm, then 170mm, now 190mm) and rims (70mm and 90mm), the Fatback bike company of Anchorage, Alaska pushed fatbikes into the future, providing more flotation with less weight. In 2010, both Surly and Salsa released complete fatbikes through the QBP distribution chain, providing another huge leap in accessibility and sales. This year, over a dozen companies are offering complete bikes. Ten years ago, this would have been hard to imagine.

The future of fatbikes is bright as new bikes and adventures make headlines each year. From 22lb carbon bikes to rack-friendly steel touring models like the classic Pugsley, there is a fatbike for everyone.

Thanks to Greg Matyas of Fatback Bikes and Speedway Cycles in Anchorage, AK for the collection of historical fatbike equipment.

—

NICHOLAS CARMAN left on a bike trip in 2008 and never stopped riding. You can find his stories, photographs, and ideas online at gypsybytrade.wordpress.com.

/image%2F0691865%2F20140730%2Fob_526867_testata950x250.jpg)

/image%2F0691865%2F201307%2Fob_1b02d7edd43804b824eacce992d488f7_102-low.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fcx.cxmagazine.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2016%2F03%2Fkhs-cxmagazine-_042-clee-v2_1-750x720.jpg)

/image%2F0691865%2F20160419%2Fob_86c466_soma-highway.JPG)

/image%2F0691865%2F20160419%2Fob_be3dad_khs-bajada-slx-15.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstatic1.squarespace.com%2Fstatic%2F558ab54be4b0250602a21727%2Ft%2F568af6b5e0327c7221144144%2F1451947712366%2FIMG_8933.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstatic1.squarespace.com%2Fstatic%2F558ab54be4b0250602a21727%2F56980a88e0327ca6778e2b97%2F56980a88e0327ca6778e2b98%2F1448887594940%2FIMG_0447.jpg%3Fformat%3D1500w)

/image%2F0691865%2F20150408%2Fob_550b40_khs-4season5000-my2015-se-01-low.jpg)

/image%2F0691865%2F20150130%2Fob_f8dabc_4season-3000-my2015-22-low.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bicycling.com%2Fsites%2Fbicycling.com%2Ffiles%2Ffat-bike-racing-2_0.jpeg)

/http%3A%2F%2Frm-content.s3.amazonaws.com%2F550369e7f7afa31d4ef411fb%2F478269%2Fscreenshot-e1080ac0-da8e-11e5-818c-7b1ed5cfc501_readyscr_1024.jpg)

Commenta il post